telejam

Introduction to Telejam

Playing music with each other and for each other, all over the world

Streaming and synchronization

There is a subtle difference between playing simultaneously (all at the same time) and being synchronized (exactly together).

Sending audio over long distances takes time. People are not always aware of this. For example, on a long distance phone call, everyone has a different experience.

When you phone a friend (SF to Paris) your friend hears you say: “how are you?” and answers back immediately: “bien”. On their side of the wire, there is no pause between your question and their answer. Your friend feels the conversation is synchronized. But on your end, after you ask “how are you?” there’s a long pause as the words go to Paris, your friend replies, and the answer comes back. What you experience is: “how are you?” … … … “bien.” There’s no way around this. It takes time to send sound back and forth on a two-way audio stream.

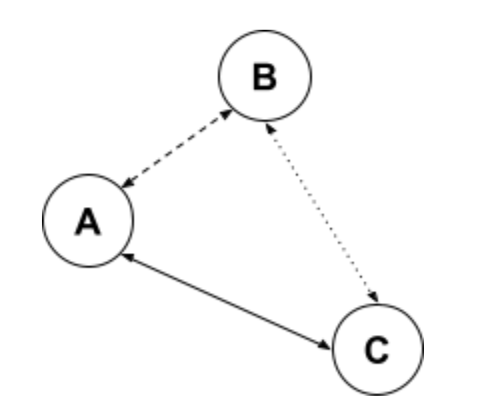

In ordinary conversation, this is not a problem. But when trying to play music together it can be difficult, especially as the distance between players increases and there are more than two players in a remotely distributed ensemble. Here’s a group of three players, all connected to each other over the internet:

The time it takes for sound to travel between players A and B and the time between A and C is probably not the same, especially if the distance between A and C is much greater than the distance between A and B. Likewise, the time between players C and B depends on the distance between them and can be different. If everyone is playing simultaneously the synchronization between them is probably loose, not exact.

General wisdom is that a 20-30 millisecond time delay between players is tolerable, but anything longer than that makes it impossible to play music together.

This is not a new problem. Musicians experience delays when playing together on a large stage, Gabrielli struggled with this in the San Marco cathedral, and players using the internet encounter the same pain. Though it’s tantalizing to be able to hear each other over long distances, the breakdown in the ability to synchronize in a musically comfortable way is discouraging.

One way streaming

Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards. Søren Kierkegaard

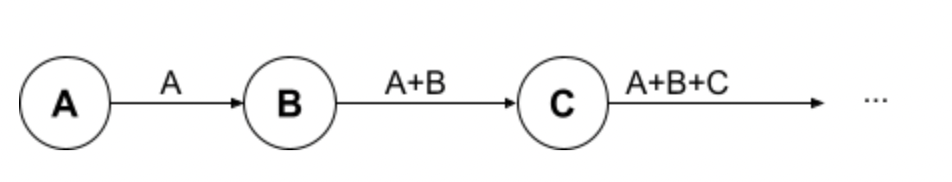

There is an alternative that preserves synchronization. Rather than transmit every player’s audio to every other player, the musicians can be arranged in a daisy chain, from left to right:

Player A sends audio to player B. Player B adds their part and the mix of A+B is sent on player C, who adds their part and sends the A+B+C mix on down the line. And so it goes.

The time it takes for sound to travel from A to B, and B to C does not matter. No matter how far apart the players are, each one hears a perfectly synchronized mix of all the players in the chain who came before them.

But there is a tradeoff: Player A, the first one in the chain, can’t hear any other players. (Any audio coming back would be out of sync and this can be annoying, confusing, or both.) Likewise, B and C hear everyone one who played “before” them, but not “after” them. At the end of the chain, the last participant hears the whole ensemble - and has no way to tell who played in what order.

A one-way stream might seem odd at first, but practically speaking, the real time assembly of the performance resembles the way many music projects are produced by multi tracking and overdubbing. Player A goes into the studio and lays down their tracks - and leaves. Later, Player B comes in, listens to A’s backing track and records their part. In turn, C arrives, plays against the pre-recorded A and B tracks, and bit by bit the project is assembled. But that takes time, and there is no interaction between players.

Using a live daisy chain, every player knows they are “in it together” and they are reacting in real time to each other. Even A knows this, who can change tempo, dynamics, etc., and might feel they are challenging or daring the players down the line to follow along. The frisson and edge of the daisy chain can feel like a live session. In an interesting way, the activity on the chain is like the old MMO (music minus one) LPs, but the growing mix passed down the line is more like OMM - one more musician. The music each successive player receives becomes richer and richer.

There is a way to make up for the lack of all-way feedback. The final mix can be recorded and immediately played back to the ensemble, who can listen to it together and discuss it over an all-way conferencing application. This is like recording a take in a studio, and going to the control room to listen to the playback with the engineer and producer.

Each player’s input can also be recorded and saved as the streaming mix is being played. Later, these tracks can be loaded into a DAW to create a new mix using the original material.

It’s interesting to note that the first player in the chain wields the power to hold the group together. Without a conductor there has to be enough information so everyone knows where the beat is. The decision on how to order the players depends on the music they are playing. There doesn’t have to be a metronome or full backing track at the start of the chain (though that’s possible if the first player has the appropriate audio setup). In many cases, players can tolerate a measured pause coming from their left. They can “flywheel” on their own and quickly adapt if they are slightly off when the first player picks up again.

The Telejam App

Telejam uses a daisy chain to connect musicians around the world without regard to the distance between them. It is a web app that runs in the Chrome browser. It requires no special hardware, software installation, or configuration. You only need:

- An internet connection (can be wired, wifi, or hotspot)

- A computer running the Chrome browser

- Headphones (wired or wireless)

- A mic or audio interface for your audio input (built-in or external)

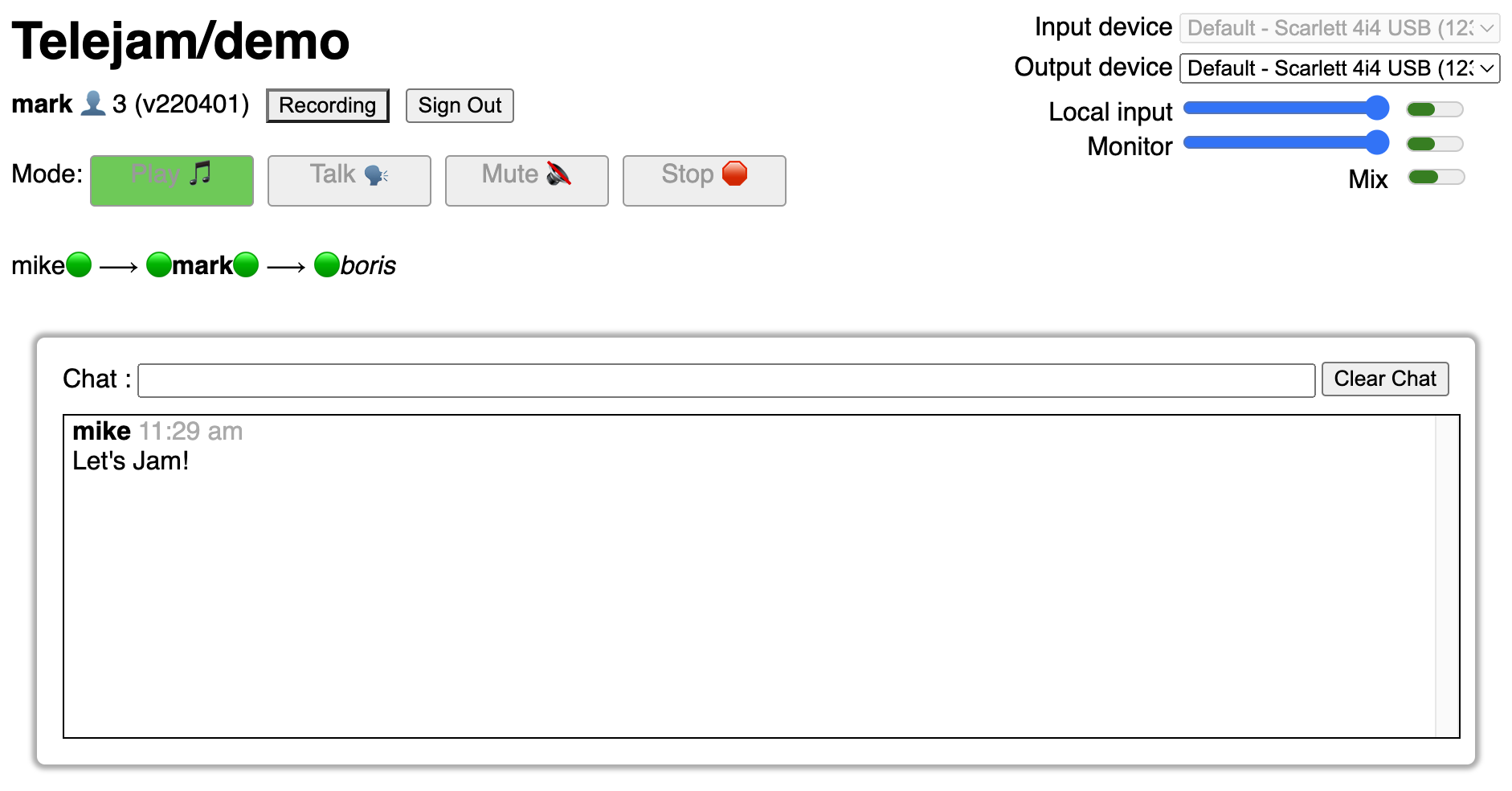

Here is the web interface seen by the second player in a three person chain:

Telejam runs audio along the chain in two modes:

- PLAY sends audio left-to-right only for synchronized performances which can be live-streamed and recorded

- TALK runs the chain in both directions to allow group conversation and unsynchronized playing

The two blue faders with meters control the player’s input level and level of the incoming mix from the players to the left. The mix meter shows the level of the player’s output mix, the sum of the input and the incoming mix which is sent on to the next player.

The chat window contains an ordinary textual chat thread. Players can use chat to exchange information that won’t disturb the audio stream. A designated player is the session leader. The leader can sit anywhere on the chain and may or may not play along. The leader performs these functions:

- Arranges the order of players

- Switches modes

- Starts and stops recording and playback

The leader can also listen to the final mix while everyone is playing and change the local input levels of each player in real time to control the balance.

Although Telejam is an audio-only application, it can run alongside a video streaming or conferencing app to provide a simultaneous video feed, which of course will not be in sync with the audio. Players should not listen to the video app, but they can see and be seen by each other and by a wider audience watching the video app. The Telejam output can be patched into the video app to send the synchronized audio to the audience.

Varieties of musical experience

Being able to play’s the thing…

Musicians are familiar with solitary solo performance. They practice alone, play along to recordings, produce tracks to be used later to assemble a finished product, and livestream themselves to an unheard and sometimes unseen audience.

Telejam is unusual because it occupies a space between a live in-person collaboration and a disembodied overdubbing session. It offers the ability to collaborate live, in the moment, with others.

Telejam is designed to support all kinds of musical activity over long distances, whether it’s only among a group of players themselves, between a teacher and one or more students, and with or without an audience. Here are some use cases:

- Casual jamming

- Rehearsal

- Live Performance

- Private lessons

- Master class

- Online choir singing for a religious service

- Tracking sessions

The Telejam story

Telejam was created by Mark Goldstein, Michael McNabb, and Boris Smus. Listen to an interview with Mark Goldstein on The Hacker Mind podcast.

If you have questions, write to markgoldstein144 (at) gmail (dot) com.

Sample recordings

- Here is a session between LA (flute), Baltimore (bass and voice - two homes), and San Francisco (percussion). Corcovado

- How about Hawaii (uke/voices), Brooklyn (bass), Oahu (keys), and San Francisco (melodica)? LoversNotion

- We jammed on a tune composed by Bobby Sturm’s Tradformer ML project. Check out Ping the Kvetch with players in Sweden, Holland, and San Francisco.

- Five movements (1,2,3,5, and 6) from Divertimento for Flute, Oboe and Clarinet by Malcolm Arnold. Performed by players from their homes in New Haven CT, Boston MA, and Bloomington IN.